Voiceless retroflex fricative

The voiceless retroflex sibilant fricative is a type of consonantal sound used in some spoken languages. The symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet that represents this sound is ⟨ В⟩ which is a Latin letter s combined with a retroflex hook. Like all the retroflex consonants, the IPA letter is formed by adding a rightward-pointing hook to the bottom of ⟨s⟩ (the letter used for the corresponding alveolar consonant). A distinction can be made between laminal, apical, and sub-apical articulations. Only one language, Toda, appears to have more than one voiceless retroflex sibilant, and it distinguishes subapical palatal from apical postalveolar retroflex sibilants; that is, both the tongue articulation and the place of contact on the roof of the mouth are different.

Some scholars also posit the voiceless retroflex approximant distinct from the fricative. The approximant may be represented in the IPA as ⟨…їћК⟩.

Features

Features of the voiceless retroflex fricative:

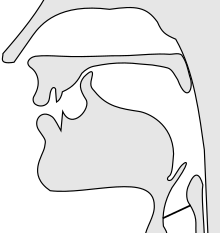

- Its manner of articulation is sibilant fricative, which means it is generally produced by channeling air flow along a groove in the back of the tongue up to the place of articulation, at which point it is focused against the sharp edge of the nearly clenched teeth, causing high-frequency turbulence.

- Its place of articulation is retroflex, which prototypically means it is articulated subapical (with the tip of the tongue curled up), but more generally, it means that it is postalveolar without being palatalized. That is, besides the prototypical subapical articulation, the tongue can be apical (pointed) or, in some fricatives, laminal (flat).

- Its phonation is voiceless, which means it is produced without vibrations of the vocal cords. In some languages the vocal cords are actively separated, so it is always voiceless; in others the cords are lax, so that it may take on the voicing of adjacent sounds.

- It is an oral consonant, which means air is allowed to escape through the mouth only.

- It is a central consonant, which means it is produced by directing the airstream along the center of the tongue, rather than to the sides.

- Its airstream mechanism is pulmonic, which means it is articulated by pushing air solely with the intercostal muscles and abdominal muscles, as in most sounds.

Occurrence

In the following transcriptions, diacritics may be used to distinguish between apical [ ВћЇ] and laminal [ Вћї].

The commonality of [ В] cross-linguistically is 6% in a phonological analysis of 2155 languages.[1]

| Language | Word | IPA | Meaning | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abkhaz | –∞–Љ—И/am≈° | [am В] | 'day' | See Abkhaz phonology | |

| Adyghe | –њ—И—К–∞—И—К—Н/p≈°√°≈°a | 'girl' | Laminal. | ||

| Chinese | Mandarin | зЯ≥/sh√≠ | [ ВћЇ…їћ©ЋІЋ•] | 'stone' | Apical. See Mandarin phonology |

| Emilian-Romagnol | Romagnol | s√© | [ЋИ ВƒХ] | 'yes' | Apical; may be [sћЇ ≤] or [ Г] instead. |

| Faroese | f√љrs | [f К В] | 'eighty' | ||

| bert | [p…Ы…їћК И] | 'only' | Devoiced approximant allophone of /r/.[2] See Faroese phonology | ||

| Hindustani | Hindi | а§Ха§Ја•На§Я/ka≈°≈• | [ЋИk…Щ В И] | 'trouble' | See Hindi phonology |

| Kannada | а≤Ха≤Ја≥На≤Я/ka≈°≈•a | [k…Р В И…Р] | 'difficult' | Only in loanwords. See Kannada phonology. | |

| Kazakh | —И–∞“У—Л–љ, ≈ЯaƒЯƒ±n | [ В…С…£…ѓn] | 'small, compact' | See Kazakh phonology | |

| Khanty | Most northern dialects | —И–∞—И/≈°a≈° | [ В…С В] | 'knee' | Corresponds to a voiceless retroflex affricate / ИЌ° В/ in the southern and eastern dialects. |

| Lower Sorbian[3][4] | gla≈Њk | [ЋИ…°l√§ Вk] | 'glass' | ||

| Malayalam | аіХаіЈаµНаіЯаіВ/ka≈°tam | [k…Р В И…Рm] | 'difficult' | Only occurs in loanwords. | |

| Mapudungun[5] | trukur | [ ИЌ° В КћЭЋИk К В] | 'fog' | Possible allophone of / Р/ in post-nuclear position.[5] | |

| Marathi | а§Ла§Ја•А/re≈°i | [rћ© ВiЋР] | 'sage' | See Marathi phonology | |

| Nepali | а§Ја§Ја•Н৆а•А/s√≥≈°thi | [s М В И ∞i] | 'Shashthi (day)' | Allophone of /s/ in neighbourhood of retroflex consonants.

See Nepali phonology | |

| Norwegian | norsk | [n…Ф Вk] | 'Norwegian' | Allophone of the sequence /…Њs/ in many dialects, including Urban East Norwegian. See Norwegian phonology | |

| O Љodham | Cuk-ấon | [t Г Кk В…Фn] | Tucson | ||

| Pashto | Southern dialect | ЏЪўИЎѓўД/≈°od√Ђl | [ Вod…Щl] | 'to show' | |

| Polish | Standard[6] | szum | 'rustle' | After voiceless consonants it is also represented by ⟨rz⟩. When written so, it can be instead pronounced as the voiceless raised alveolar non-sonorant trill by few speakers.[7] It is transcribed / Г/ by most Polish scholars. See Polish phonology | |

| Southeastern Cuyavian dialects[8] | schowali | [ Вx…ФЋИv√§li] | 'they hid' | Some speakers. It's a result of hypercorrecting the more popular merger of / В/ and /s/ into [s] (see szadzenie). | |

| Suwa≈Вki dialect[9] | |||||

| Romanian | Moldavian dialects[10] | »ЩurƒГ | [' Вur…Щ] | 'barn' | Apical.[10] See Romanian phonology |

| Transylvanian dialects[10] | |||||

| Russian[6] | —И—Г—В/≈°ut | [ Вutћ™] | 'jester' | See Russian phonology | |

| Serbo-Croatian[11][12] | —И–∞–ї / ≈°al | [ »Þ†l] | 'scarf' | Typically transcribed as / Г/. See Serbo-Croatian phonology | |

| Slovak[13] | ≈°atka | [ЋИ В√§tk√§] | 'kerchief' | ||

| Swedish | fors | [f…Ф В] | 'rapids' | Allophone of the sequence /rs/ in many dialects, including Central Standard Swedish. See Swedish phonology | |

| Tamil | аЃХаЃЈаѓНаЃЯаЃЃаѓН/ka≈°tham | [k…Р В И…Рm] | 'difficult' | Only occurs in loanwords, often replaced with /s/. See Tamil phonology | |

| Telugu | а∞Ха∞Ја±На∞Яа∞В/ka≈°tam | Only occurs in loanwords. See Telugu phonology | |||

| Toda[14] | [p…Ф В] | '(clan name)' | Subapical, contrasts /ќЄ sћ™ sћ† Г Т В Р/.[15] | ||

| Torwali[16] | ≈°e≈°/ЁЬџМЁЬ | [ Вe В] | 'thin rope' | ||

| Ubykh | [ ВћЇa] | 'head' | See Ubykh phonology | ||

| Ukrainian | —И–∞—Е–Є/≈°ahy | [ЋИ В…Сx…™] | 'chess' | See Ukrainian phonology | |

| Upper Sorbian | Some dialects[17][18] | [example needed] | вАФ | вАФ | Used in dialects spoken in villages north of Hoyerswerda; corresponds to [ Г] in standard language.[3] |

| Vietnamese | Southern dialects[19] | sбїѓa | [ В…®…ЩЋІЋАЋ•] | 'milk' | See Vietnamese phonology |

| Yi | кПВ/shy | [ ВћЇ…єћ©ЋІ] | 'gold' | ||

| Yurok[20] | segep | [ В…Ы…£ep] | 'coyote' | ||

| Zapotec | Tilquiapan[21] | [example needed] | вАФ | вАФ | Allophone of / Г/ before [a] and [u]. |

Voiceless retroflex non-sibilant fricative

Features

Features of the voiceless retroflex non-sibilant fricative:

- Its manner of articulation is fricative, which means it is produced by constricting air flow through a narrow channel at the place of articulation, causing turbulence.

- Its place of articulation is retroflex, which prototypically means it is articulated subapical (with the tip of the tongue curled up), but more generally, it means that it is postalveolar without being palatalized. That is, besides the prototypical subapical articulation, the tongue can be apical (pointed) or, in some fricatives, laminal (flat).

- Its phonation is voiceless, which means it is produced without vibrations of the vocal cords. In some languages the vocal cords are actively separated, so it is always voiceless; in others the cords are lax, so that it may take on the voicing of adjacent sounds.

- It is an oral consonant, which means air is allowed to escape through the mouth only.

- It is a central consonant, which means it is produced by directing the airstream along the center of the tongue, rather than to the sides.

- Its airstream mechanism is pulmonic, which means it is articulated by pushing air solely with the intercostal muscles and abdominal muscles, as in most sounds.

Occurrence

| Language | Word | IPA | Meaning | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angami[22] | …їћ•…Щ¬≥ | […їћ•…ЩЋ®] | 'to plan' | Contrasts with /…ї/ | |

| Chokri[23] | [t…Щ…їћ•…®Ћ•ЋІ] | 'sew' | In free variation with /ѕЗ/; contrasts with /…ї/ | ||

| Ormuri[24][25] | Kaniguram dialect | su≈Щ | [su…їћЭћК] | 'red' | Usually corresponds to / Г/ in the Logar dialect |

See also

Notes

- ^ Phoible.org. (2018). PHOIBLE Online - Segments. [online] Available at: http://phoible.org/parameters.

- ^ √Бrnason (2011), p. 115.

- ^ a b ≈†ewc-Schuster (1984), pp. 40вАУ41

- ^ Zygis (2003), pp. 180вАУ181, 190вАУ191.

- ^ a b Sadowsky et al. (2013), p. 90.

- ^ a b Hamann (2004), p. 65

- ^ Kara≈Ы, Halina. "Gwary polskie - Frykatywne r≈Љ (≈Щ)". Archived from the original on 2013-11-13. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ Taras, Barbara. "Gwary polskie - Gwara regionu". Archived from the original on 2013-11-13.

- ^ Kara≈Ы, Halina. "Gwary polskie - Szadzenie". Archived from the original on 2013-11-13.

- ^ a b c Pop (1938), p. 31.

- ^ KordiƒЗ (2006), p. 5.

- ^ Landau et al. (1999), p. 67.

- ^ Hanulíková & Hamann (2010), p. 374.

- ^ Ladefoged (2005), p. 168.

- ^ Krishnamurti (2003), p. 66.

- ^ Lunsford (2001), pp. 16вАУ20.

- ^ Šewc-Schuster (1984), p. 41.

- ^ Zygis (2003), p. 180.

- ^ Thompson (1959), pp. 458вАУ461.

- ^ "Yurok consonants". Yurok Language Project. UC Berkeley. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ Merrill (2008), p. 109.

- ^ Blankenship, Barbara; Ladefoged, Peter; Bhaskararao, Peri; Chase, Nichumeno (Fall 1993). "Phonetic structures of Khonoma Angami" (PDF). Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area. 16 (2): 87.

- ^ Bielenberg, Brian; Zhalie, Nienu (Fall 2001). "Chokri (Phek Dialect): Phonetics and Phonology" (PDF). Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area. 24 (2): 85вАУ122. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ Nov√°k, ƒљubom√≠r (2013). "Other Eastern Iranian Languages". Problem of Archaism and Innovation in the Eastern Iranian Languages (PhD dissertation). Prague: Charles University. p. 59.

This sound can be transcribed also бє£ћМ ≥, the sound should be similar to Czech voiceless ≈Щ (Burki 2001), phonetically […їћЭћК]: voiceless retroflex non-sibilant fricative. Similar sound but voiced occurs also in the N≈ЂristƒБnƒЂ languages

- ^ Efimov, V. A. (2011). Baart, Joan L. G. (ed.). The Ormuri Language in Past and Present. Translated by Baart, Joan L. G. Islamabad: Forum for Language Initiatives. ISBN 978-969-9437-02-1.

...and ≈Щ for the peculiar voiceless fricativized trill that occurs in the Kaniguram dialect.... In the original work, Efimov followed Morgenstierne in using бє£ћМ ≥ to represent this sound, which has been replaced here with the typographically simpler бєЫћМ.

References

- √Бrnason, Kristj√°n (2011), The Phonology of Icelandic and Faroese, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-922931-4

- Canepari, Luciano (1992), Il M¬™Pi вАУ Manuale di pronuncia italiana [Handbook of Italian Pronunciation] (in Italian), Bologna: Zanichelli, ISBN 88-08-24624-8

- Hamann, Silke (2004), "Retroflex fricatives in Slavic languages" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 34 (1): 53вАУ67, doi:10.1017/S0025100304001604, S2CID 2224095, archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-14, retrieved 2015-04-09

- Hanul√≠kov√°, Adriana; Hamann, Silke (2010), "Slovak" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 40 (3): 373вАУ378, doi:10.1017/S0025100310000162

- Ladefoged, Peter (2005), Vowels and Consonants (2nd ed.), Blackwell

- Lunsford, Wayne A. (2001), "An overview of linguistic structures in Torwali, a language of Northern Pakistan" (PDF), M.A. Thesis, University of Texas at Arlington

- Merrill, Elizabeth (2008), "Tilquiapan Zapotec" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 38 (1): 107вАУ114, doi:10.1017/S0025100308003344

- Pop, Sever (1938), Micul Atlas Linguistic Rom√Ґn, Muzeul Limbii Rom√Ґne Cluj

- Sadowsky, Scott; Painequeo, H√©ctor; Salamanca, Gast√≥n; Avelino, Heriberto (2013), "Mapudungun", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 43 (1): 87вАУ96, doi:10.1017/S0025100312000369

- ≈†ewc-Schuster, Hinc (1984), Gramatika hornjo-serbskeje rƒЫƒНe, Budy≈°in: Ludowe nak≈Вadnistwo Domowina

- Thompson, Laurence (1959), "Saigon phonemics", Language, 35 (3): 454вАУ476, doi:10.2307/411232, JSTOR 411232

- Zygis, Marzena (2003), "Phonetic and Phonological Aspects of Slavic Sibilant Fricatives", ZAS Papers in Linguistics, 3: 175вАУ213, doi:10.21248/zaspil.32.2003.191

- KordiƒЗ, Snje≈Њana (2006), Serbo-Croatian, Languages of the World/Materials; 148, Munich & Newcastle: Lincom Europa, ISBN 978-3-89586-161-1

- Landau, Ernestina; LonƒНariƒЗ, Mijo; Horga, Damir; ≈†kariƒЗ, Ivo (1999), "Croatian", Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 66вАУ69, ISBN 978-0-521-65236-0